“The reasonable man adapts himself to the world: the unreasonable one persists in trying to adapt the world to himself. Therefore all progress depends on the unreasonable man.”- George Bernard Shaw, Man and Superman

Salvador Dali stunk of undiluted narcissism, and yet he was unashamed. Any acquaintance of Dali’s could, without difficulty, rattle off a list of his pompous pronouncements. He was endlessly exalted, perennially proud; was said to wake up every morning “astonished at the sublime nature of every facet of hisexistence, to the point of wondering how anybody else could possibly survive without being him.” His self-aggrandizement was believed to be the last straw of his friendship and affinity with the Surrealists. Andre Breton, the founder of Surrealism, dubbed Dali the “Avida Dollars,” an anagram for his name, which means “eager for money.” Dali’s blatant pursuit of commercialism and fame was especially an anathema to his fellow Surrealists, who were noted for their ostensible indifference to anything considered voguish in the present cultural scene. Feeling piqued at Dali’s incessant waywardness and increasing popularity, the Surrealists ultimately terminated the artist’s involvement with the art movement.

In my opinion, the term “surreal” is never the most apposite to encapsulate Dali’s paintings. The idea of “surreal” entails something that is preternatural, something that is unfamiliar to our limited knowledge. Dali’s visionary world is, though at first glance grotesque, in fact oddly familiar. In Still Life Moving Fast (1956) Dali attempted to capture the swiftness of movement with his paintbrush. Every object is up in the air in disarray, but there seems to be an underlying rhythm that unites them all into a discordant symphony. There is the trickle of water that sprints out from the jar, traverses mid-air in swirls, and curves around the goblet as its journey ends. There is the apple and the cherry which, when triggered by the violent jerk, gather such momentum that leave in their wake blinding shafts of light. A knife floats dangerously up; its silhouette slants through the tablecloth in perfect symmetry with the blade. In view, the painting resembles Cezanne’s Still Life with Cherub (1895), both of which experiment with the possibility of freezing a flurry of succeeding movements. In kind, it recalls James Whistler’s pictorial transcription of music.

Dali hadn’t done what had not already been done before. His “dream-images” are rarely dreamlike. Most of the artworks assume an almost austere formality that seemed more likely to be done in sobriety and consciousness. Unlike his fellow Surrealists, Dali wasn’t one to undermine the value of traditional aesthetics. A large amount of his artistic output is dominated by religious and allegorical paintings. Dali’s treatment of religious themes is often branded the prototype of “kitsch,” again a label I’m incredulous of. For me, Dali’s interpretation of the Scripture seemed centering on a harmonious integration of the universe and the deities, something that Leonardo da Vinci would have resonate with. In his rendition of The Last Supper, the traditional setting of a walled-in refectory is substituted with a transparent dodecahedron. In it twelve apostles sit bowed to Christ, who points with His forefinger to a floating torso above him, seeming to hint at his own spirit, prefiguring the destiny of His life. With the descending of the light, invading into the transparent refectory on all sides, everything within is rendered peculiarly diaphanous- the food, the table, the robes of the apostles. Every one seems sooner to join with Christ on His ascendancy to Heaven. “Nothing lasts forever. Everything fades away,” a voice seems to say, booming from the rocks that stand immutably at the perceivable horizon.

Artworks that were produced during the height of Modernism were invariably set into the context of the advancement of technology. Viewers saw in the paintings various unnamable, ill-formed beasts like the monstrous, horrendous machines that marched menacingly towards them. Artists deftly exploited the fear and anxiety that were common to the age, and conferred on their artworks feelings of unease and callousness. Amongst them, however, Dali was never inclined to be as yet another tormentor. But he was unequivocally a prophet. He saw men extracted of their souls, their calcified skulls marooned on the deserts, the hollowed-out sockets providing ample spaces for other skulls to dwell in. In a particularly agonising sight, a man has his body twist and pull into an extremely grotesque shape. His face grimaced with excruciating pain. We feel vicariously his misery. We commiserate with his wretched condition. But we do not want to have a second glance of it.

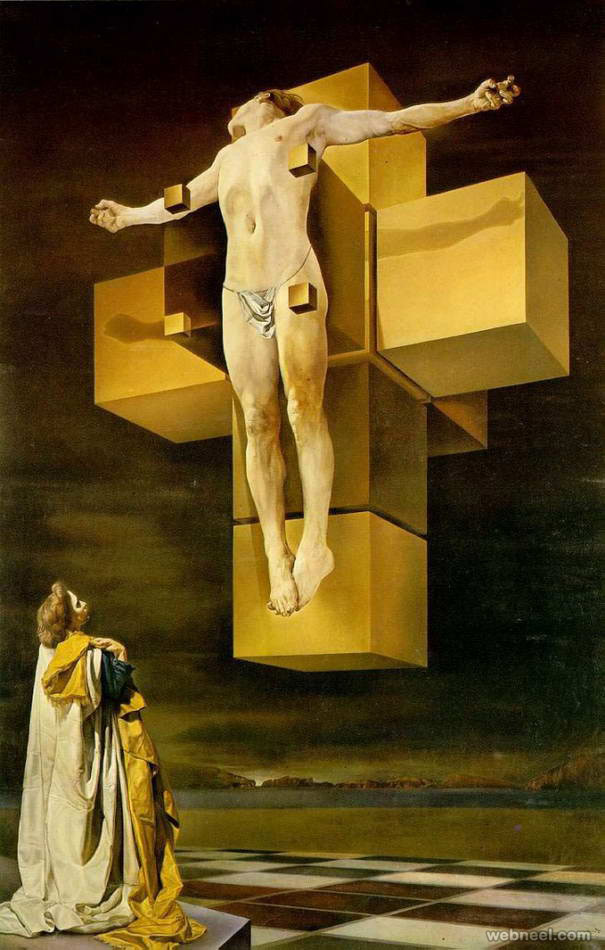

If this is what living in the modern age entails, namely that people are increasingly distancing from each other without explicit reasons, that the ceaseless popping-up of new inventions will one day replace the renewal of our virtues, that one day, not in a very distant future, our spirit and our body will be separated and cast stranded on a desert created by our own hands. The seemingly fantastical visions that Dali created have an underlying message that is rather poignant. InCrucifixion (1954), Christ is suspended on a crucifix made by golden hypercubes. A woman at the bottom looks up at the imposing figure in a manner that most of us can certainly identify with when we are viewing a masterpiece: awed, transfixed, but always maintain a respectable distance with the work, always tend to ennoble it to an elevated state that is forever out of our reach. I see in every of Dali’s paintings a projection of his own self- extremely narcissistic, extremely self-vaunted, extremely mischievous, and yet extremely lonely and paranoid. To adapt the world to oneself means to build inside of one an unpopulated world, with himself as the only occupant. Dali lived in such a world.

No comments:

Post a Comment